The hospital of St Mary Magdalen

One of three Grade I listed buildings in Ripon

The Chapel is open every day from 10am till 4pm. Sunday service is from 10am till 1130am. From the cathedral turn right onto Minster Road, bear left onto St Marygate, cross at the traffic lights onto Stonebridgegate, past Aldi, straight on to Magdalen Road 150 mts on the right and left.

Artist's impression of the hospital of St Mary Magdalen in around 1830. The chapel roof is below the parapet and unseen. The central of the three windows in the south wall is blocked up and the Norman doorway has a round headed door rather than the present pointed insertion (artistic licence?) Beside the west end of the chapel are three stone cottages built in the latter half of the C18th and demolished about 1898. On the left, across the road from the chapel, are the six almshouses built in 1674 which replaced the chapel building as the accommodation for the residents. They were demolished in 1875.

The chapel of St Mary Magdalen today

The hospital of St Mary Magdalen was probably built in the 1130s on land given by Thurstan, Archbishop of York 1119-1140, and is the oldest building in Ripon It was founded to care for lepers, travellers and the local destitute. It formed a small community with the stone hospital, assorted wath and plaster buildings all surrounded by a fence with a high gateway to allow haycarts through. There were farm buildings, the master's house, a house for the priests, a dovecote, service buildings such as kitchen, buttery and brewhouse, and possibly an infirmary.

The stone building (now the chapel) was a dormitory and living quarters with an altar at the east end. The building saw an upgrade in medieval times to further separate the altar from the living quarters. It appears to have been enlarged at the east end where limestone from Quarry Moor has been used. The two windows, east and south are in "perpendicular style", probably C15th. Other windows are earlier, possibly C12th. The east window is primitive work being lop-sided and wrongly proportioned.

At the time of this building work the roof was replaced with one of very low pitch, set on walls strengthened at their tops with limestone blocks to form a parapet. These blocks were also used in the bell cote and the buttress below it on the west wall, which may also have been added at this time.

Until the 1860s, some masters allowed hospital buildings to become derelict rather than spend money on their upkeep. In 1674 the new master, Richard Hooke, found the buildings so derelict he had them demolished, leaving only the chapel building and the master's house. He provided accommodation for the residents by building six almshouses on the opposite side of the road.

Almshouses had become popular in Tudor times after Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries and the closure of their associated hospitals. They provided more privacy and independence than the hospital arrangements.

In 1864 a new form of management was introduced to to the hospitals of St Mary Magdalen and St John the Baptist after a 41 year long court case. Management of the hospitals would be by a board of trustees, answerable to the newly formed Charity Commission. A scheme was drawn up by which the Hospitals and Chapels would be run. A report to the trustees in 1866 suggested that the two chapels needed a lot of money to make them useable. The Trustees decided to demolish the chapel of St John the Baptist and build a new one. They had no money to repeat the exercise at St Mary Magdalen, but one of the trustees, George Mason of Copt Hewick Hall, offered £12,000 (over £1 million today) to repair or rebuild the chapel. He chose to rebuild on a new site, but not to demolish the Norman chapel. The new chapel was built across the road behind the 1674 almshouses.

The almshouses built in 1674 at the request of the master, Richard Hooke. They were replaced in 1875.

New Management of the hospitals.

The new chapel. Grade II listed

When the new chapel opened in 1869, the Norman chapel was closed and remained little used for 120 years. The trustees continued to maintain it and, while it had periods of semi-dereliction, it was not allowed to decay. Neither was it subjected to Victorian ideas of "beautification". So, in 1989 when it was discovered the damp and crumbling Victorian chapel was consistently more expensive to maintain than the Norman chapel, it was decided to sell the new chapel and move back into the Norman building. This move was made in 1989 and the Victorian chapel is now a private house and is not open to the public.

The Norman Chapel

Windows in the north wall. The smaller window on the right is C12th, the larger on the left is C15th and probably part of the extension eastwards. The smaller window is set low in the wall and there has been debate over whether or not it was a leper window (hagioscope) through which lepers could see mass at the altar and possibly receive communion. Arguments for the idea include the position of the window low in the wall, it looks to the area north of the chapel where the leper house had been built, and, if the chapel was lengthened in C15th the altar of the original chapel would have been in clear view from outside through the low window.

The doorway to the left of the windows has been blocked up. It would have led into the chancel. There is some evidence of a small room built onto this end of the north wall and it may have been a chantry chapel. St Mary Magdalen's hospital had two chantries, money given by local people to employ a priest to pray for their souls and the souls of family members and, in this case, "for all Christian soulz". One of the chantries was given by John Warrener of Studley, a nearby estate. At one time St Mary Magdalen had five priests and accommodation had been built for them to live in. Chantry priests and the chaplain had different points of entry to the chapel, the chaplain using the south door, the chantry priests possibly using the entry from the chantry chapel.

Image from the Luttrell Psalter

The "font" is medieval and stands on a modern base. It was found in a local field and returned to the chapel in the 1950s. Why did a leper hospital chapel need a font? Baptisms anyway were only allowed in parish churches and at a cost. Expert opinion resolves the issue. It is not a font, it is a medieval mortar for grinding grain using a pestle and probably from an Abbey. Fountains?

The stone medieval altar is a rare survivor, one of only three in the country. At the Reformation, Henry VIII ordered all stone altars to be broken and replaced with wooden tables. While this altar is broken across the middle it has been kept in service on three substantial pillars of stone.

In front of the altar is a mosaic which is thought to be Roman, possibly from a local villa.

Altars had a cross at each corner and one in the middle. Here the break in the altar has run through the middle cross so only one arm can be seen.

The altar is covered in graffiti, most likely from the civil war period. Sadly the inscribers neglected to date their work. I and B could have had a love interest, Neville is a well known local name, the cross is a saltire, presumably scratched in by a passing Scot. GeorgeBrowne must have had little else to do.

Another broken stone altar is set into the floor of the chancel under the south window. There is no clue as to where it came from. It is possible, if a chantry chapel existed outside the blocked chancel doorway, it may be from that, rescued just before the Reformation when chantry chapels were forbidden. In a plan of the chapel of St Mary Magdalen produced by a trainee architect from York, he has drawn this altar with its five crosses as he would have seen it.

The surround of the south doorway is Norman although the pillars on either side are missing. The detail shows the chevrons in the tympanum, just under the semi-circular archivolt which are weathering quickly. A later pointed door (gothic) has been inserted.

The North doorway contains a very old door, date unknown, in a pointed arch. The door is constructed of two layers of wooden planks. those on the outside running vertically and those on the inside horizontally.

Of the three windows in the south wall, the two nearest the south door are the oldest. The one on the right is of similar age to the leper window, C12th. The one on the left has been heavily restored

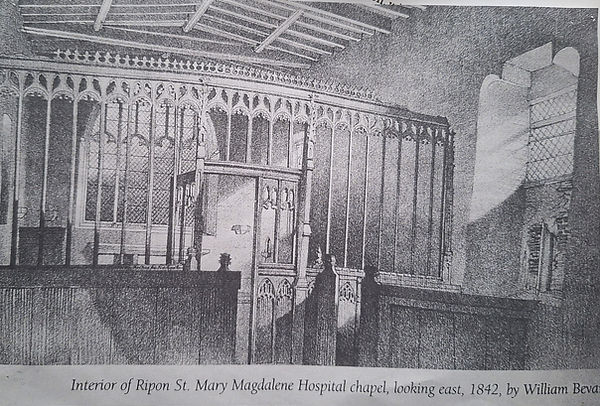

The sketch of the inside of the chapel in 1842 shows some detail of this modified window. The lower half has been "bricked" up but it still retains the base of a central mullion which, at its top, would have been likely to divide into a three pointed transom. The sketch also reveals the absence of the small early window immediately behind screen, also blocked up and covered over.

The lintel that has replaced the transom is a reused memorial stone of a priest. Look up from the inside of the window to see the markings of a chalice (on the left) and a staff (bottom and right). (see the photograph below showing the detail of the lintel stone)

Was there a building on this site before the Norman chapel?

There are a number of Saxon stones built into the structure of the chapel. They are all red sandstone, which may have come from quarries near Hutton Conyers. The carved stone is thought to be from the shaft of a Saxon cross.

The bones were revealed in six shallow graves uncovered when laying a pipe from the road to the north wall of the chapel in 1989. The bones were the subject of a Coroner's report which stated they should be reburied as near as possible to where they were dug up. However, the bones were not returned to the chapel, but to the cathedral vault and forgotten about. As no reburial was recorded, two or three members of the chapel congregation spent time, over two years, trying to locate them. In 2024 they were found in a cardboard board box labelled "St Mary Magdalen". They were finally buried, with due ceremony, 35 years late! Carbon dating of the bones reveals they were from the eighth or ninth century.

So, we have Saxon stones and Saxon people suggesting activity on the site.

The screen across the centre of the chapel is C15th, but much repaired. The two doors and their ironwork appear to be original. In 1887 the screen was removed to the cathedral after the chapel was closed in 1869. It was returned in 1897, but placed across the chapel just inside the south door.

Sketch of the old chest with a wooden bell resting on the top. The chest was possibly Jacobean and is regularly referred to in accounts of the chapel. In 1887, during the closure of the chapel (from 1868 to 1989) the chest was removed to the cathedral and, ten years later, returned to the new chapel of St Mary. It was sold by the trustees, in 1997, to an antique dealer because it was "surplus to requirements".

A wooden bell?

Not surprisingly, there is a story attached to the wooden bell. Trigger warning; it may not be true!

In the late 18th or early 19th century two young boys climbed onto the chapel roof to ring the bell. To their surprise the metal bell had gone and had been replaced with a wooden version. The issue was reported and an inquiry held. The suggestion was that an unscrupulous Master of the hospital had removed and sold the metal bell and replaced it with the wooden one so people would not notice the missing bell.

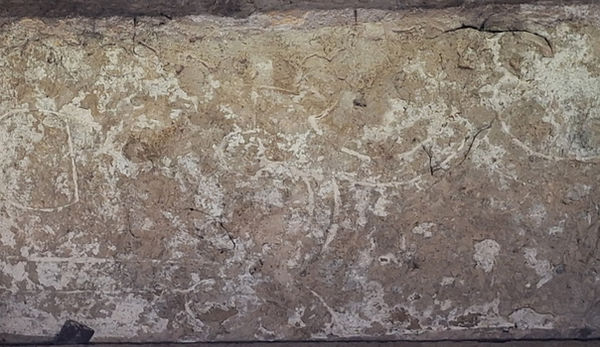

The wall painting was revealed during restoration. It was found under plaster when the plaster was being removed from the walls of the chancel. Date is, so far, unknown.

Poppyhead pew ends. These will have been carved in the C15th. It is possible they represent one of the masters of the hospital, Thomas Kempe, master from 1445 to 1450. He moved on from St Mary Magdalen to become Bishop of London. The photograph on the left appears to be of a Bishop. On the right is the reverse of that head on which is carved three wheat sheaves. The coat of arms of the Kempe family bears the same three sheaves.

The bell cote is probably 15th century, built when the east end of the hospital was lengthened. The limestone in the structure matches the limestone in the lengthened south wall, parapet and the bastion on the west wall below the bell cote. The bell was retrieved from the decommissioned Victorian chapel in 2001, recast in 2011 and rehung in the restored bell cote in 2012.

The seal of the hospital of St Mary Magdalen.

The seal is made of wood and shows St Mary Magdalen holding a jar of ointment in one hand and a book in the other.

The inscription around the side reads;

MAGDALENE RIPOVN

HOSPITALIS BTA MARIE

BTA = beata (blessed)

Almshouses

In 1875 the six almshouse built in 1674 were demolished and replaced with six new ones built with money given by the Marquess of Ripon as part of a long drawn out dispute with the trustees about an exchange of land originally agreed between the uncle of the Marquess and the Master in 1859. The footprint of the new almshouses was at right angles to the old. The Victorian chapel can be seen in the background.

In the 1890s the trustees found they had sufficient money to build more almshouses and another six were added in 1898, built of stone. These are now four as each of two pairs have been combined into one for double occupation.